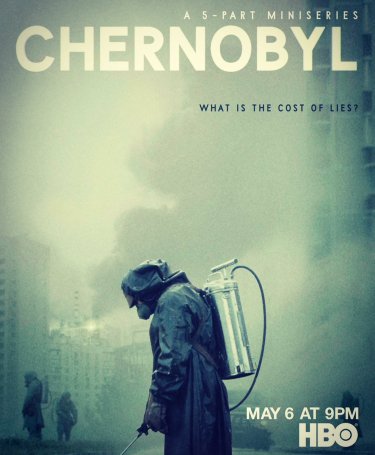

Television * Craig Mazin * Nuclear Disaster, Political Fallout * 2019

Synopsis

Everyone needs to see this.

I’m convinced of this, and despite my worries about coming off as hyperbolic I’ll stand by it. This HBO miniseries is Proper Noun Important. Yes, the disaster that the show depicts is basically ancient history now, 1986 may as well have been five hundred years ago, but the aftermath of what happened and the political reaction to it are painfully relevant. Also, it’s real easy to forget that the explosion at Chernobyl caused damage that will not be remedied in our lifetime. Or, actually, many lifetimes. Radiation is bitch, y’all. Of course, what makes Chernobyl truly special is simply how well done it is. This is such a beautifully crafted piece of media I’m having difficultly really wrapping my mind around it. Of course, considering what it’s about, it’s also an extremely grim experience. It’s one well worth having though.

Considering my deep and persistent interest in apocalyptic visions, particularly that of nuclear annihilation – I’m not weird you’re weird! – I knew shockingly little about Chernobyl before watching this. To be fair, the incident occurred when I was seven, but still, you’d think I’d have read up on it before now. Alas no, my entire knowledge of the disaster was gained through cultural osmosis. Essentially there was an explosion at a big Soviet nuclear power plant and it irradiated a huge swath of the country. And yes, that’s what happened. But what makes this show so fascinating and upsetting and important is everything surrounding the accident. Not just figuring out the how and why of the thing, but the immediate response to it and the attending political aftermath. Chernobyl takes the time to lay out not only what physically happened on site, but the very human reactions to the disaster.

Evil PF Tompkins here is a real piece of work.

What makes Chernobyl resonate is the fact that it is a dramatization rather than a documentary. Look, I love documentaries. But there is a power to dramatic storytelling that is missing from slideshow narrations. Over the course of five taut episodes, we follow the efforts of a Soviet scientist named Valery Legasov as he is tasked with “fixing” Chernobyl after the explosion. He’s our touchpoint, our anchor, this sad, frustrated, beleaguered man with an impossible job. Surrounding him are a sampling of other characters who do exceptional work in humanizing this disaster which is so vast in scope. There’s clueless bureaucrats, arrogant KGB idiots, lots of brave, doomed workers, brilliant scientists, and of course more clueless, cynical bureaucrats. All of these people work in tandem to illustrate what happened in concrete, human terms instead of cold-blooded abstraction. And sure, there’s a couple of story-telling liberties taken. But still. It’s one thing to describe the cost of this disaster with lots of numbers and statistics. It’s quite another to watch someone die of radiation sickness.

As I said, watching Chernobyl is a grim experience well worth having. It is the best disaster movie ever made. It is also a taut political drama, and a medical drama, and a courtroom drama. Episode two has one of the most affective horror scenes I’ve ever seen. Like, just thinking about it – at ten in the morning on a bright summer day – still fucks me up. Everything Chernobyl does, it does nearly perfectly. All of the science is extremely accurate, and explained simply but well. All of the details of Soviet life in the ‘80s appear to be correct. The only real issue is the fact that everyone speaks in pleasant British accents, but considering the alternatives were either subtitles (death for popular media, even now) or forced Eastern European accents, it’s fine. Also, that’s the most critical thing I have to say about it. Chernobyl is one of the best things I’ve ever seen, full stop.

Smoke, but radioactive death-smoke. This show, man.

Discussion

If humanity cannot learn to humanize abstractions, it will undo itself. That is a very fancy way of saying that we, humans, need to get our shit together or we will die. Chernobyl is an illustration of what happens when things progress beyond a human scale and fail. It’s a paradox, because we are able to create things on a scale which is beyond any single individual’s ability to comprehend concretely. Nuclear power in and of itself is an abstract concept made reality. In order to make a nuclear power plant happen, the resources of millions of people are needed, whether or not they even understand what they are supporting. This kind of scale only makes sense in an abstract way. There’s a fundamental detachment that happens when we think about it. I can’t picture a hundred thousand individual faces and neither can you, we’re simply not programmed to do so. And when we lose that individuality, it becomes easy to dismiss basic humanity. This is what happens throughout Chernobyl.

First, the physical, acute, actual danger of radiation. Over and over again Chernobyl presents situations that simply make no sense to most people, and those people are killed because their inability to take abstractions seriously. From the beginning, in the control room filled with people who should know better, there is a refusal to accept reality. The core explodes, which isn’t supposed to be able to happen, so therefore it didn’t happen, even though it clearly and obviously did. Outside, people who should probably know how radiation works (considering they live and work around a giant nuclear plant) do not, because officially there’s no danger. Then, when literally the most dangerous substance on earth is just lying around on the ground, there is no frame of reference for it. Dozens of people rush to watch a fire while death gently snows on their heads. A firefighter’s wife clings desperately to her radioactive husband with no ability to understand that she’s risking death for herself. Worst of all, Soviet officials are still placing their political careers above the lives over millions of people.

Science heroes!

After all is said and done, the political situation surrounding the events of Chernobyl is the most harrowing. Obviously radiation is terrifying. Invisible murder rays which can liquefy you if strong enough and zap cancer into you at lower doses? Yeah, no thanks. Still, it can be dealt with. The problem is, since all of this is beyond the individual scale and is happening on the social scale, you need individuals to think beyond their own immediate interests and connect the abstract to the concrete. Many people lack the ability to do this. One of my favorite scenes is when Legasov meets Boris Shcherbina (ugh, these names are impossible), a high-ranking Soviet official. Legasov is one of these incorrigible truth-tellers, which is not the Soviet way. Boris knows the game, and wants nothing to do with Legasov. As they’re flying to Chernobyl, he asks Legasov to explain how a nuclear power plant works. He does so in simple terms. To which Boris replies: “Now I know how a nuclear power plant works, and I don’t need you.” Now, Boris goes on to actually understand the situation and works to fix it, sacrificing a good deal of his health in doing so. But this is only after spending time on the ground, watching events unfold in front of him.

Boris is eventually able to see past the thing that very well might kill us all, which is individual self-interest over the interests of a vast, abstract society. After the immediate threat is dealt with, more or less, the ongoing threat is still there. Which is to say the design flaw in the RBMK reactor which led to the disaster in the first place and is common throughout the Soviet Union. When faced with that danger, the choice is pretty clear: lie and say there is no threat and that the Soviet Union is incapable of such an error, and therefore there is nothing to fix, or accept responsibility and fix the flaws. It’s obvious what the right answer is. Fix the reactors and avoid something like Chernobyl from ever happening again. It’s also obvious what answer the Soviet Union chose. Those in charge, be it the KGB or local party loyalists, have a vested interest in protecting themselves at the expense millions of people whose faces they can’t actually picture.

The most ominous structure fire in history.

The reason why Chernobyl is Important isn’t just because the Soviet Union was so clearly flawed and corrupt. It was, of course, but such things are not unique to Russia. The show rings true because the Soviet Union was made up of people, just like any place else. And the people in power there weren’t any different than people in power pretty much anywhere else. Their first priority, now and forever, is the preservation of their own power. If one must ignore clear and obvious evidence in order to preserve that power, then so be it. It millions must be imperiled so that a handful of men may continue to thrive, then that’s what will happen. If the only truth that matters is what the powerful are saying at the moment they’re saying it, then we are done as a species. Because they will say and do whatever is required to preserve their own place in the world. After all, you don’t have to look very far to see people willing to burn everything to the ground so long their interests are protected. For the time being, at least.