And here you can find the rest of the The Waste Land Project.

The Good News * Alpha and the Omega * Various Apocalypses * ∞

Synopsis

I’ve been delaying the writing of this post for quite a while. My copy of the King James has been sitting on my desk since I finished reading it, late last year. It took me the entirety of 2018 to force myself through the entire thing, one verse, one chapter, one book at a time. I did not have much fun doing that, but really it was more an exercise in discipline than anything. Also, despite the promises of many religious acquaintances throughout my life, I did not find myself moved by the Holy Spirit. It’s almost as if an ancient book about murder and treachery and infidelity and slaughter isn’t terribly inspiring. Plus there’s the fact that I chose the King James to try and bulldoze through. My reasoning was pretty straightforward, in that the King James is the traditional, literary text that most canonical English writers were familiar with. It’s a nightmare. A peculiar, bloated, repetitive nightmare. One of my main takeaways from finally getting through the Scriptures is just how many times I read the same thing, over and over and over again. You’d think the major players would have figured it out. Like yo, God hates it when you check out other gods. They never figure it out.

I’m going to do my best to avoid making the typical stale observations of a nonbeliever reading a religious text. Yes, it is a repetitive slog, but for various historical reasons that makes sense. You want the fledgling followers to really get it pounded into their heads that there is only one true god. Also, it helps to keep in mind that for the vast majority of history, The Bible was a one-way interaction. Most people were illiterate, so they were just hearing variations of these stories and parables and whatnot. The repetition is baked in to ensure not only memorization, but eventual obedience. This thing isn’t a book to be read straight through. If you keep the historical aspect of the text in mind, it makes a little more sense as to why the one true god is such a petty little whiner, pitching divine temper tantrums all the damn time. Yes, there are many guides to moral living throughout, but the primary motivator for The Bible is to ensure that you focus on this god as the only god.

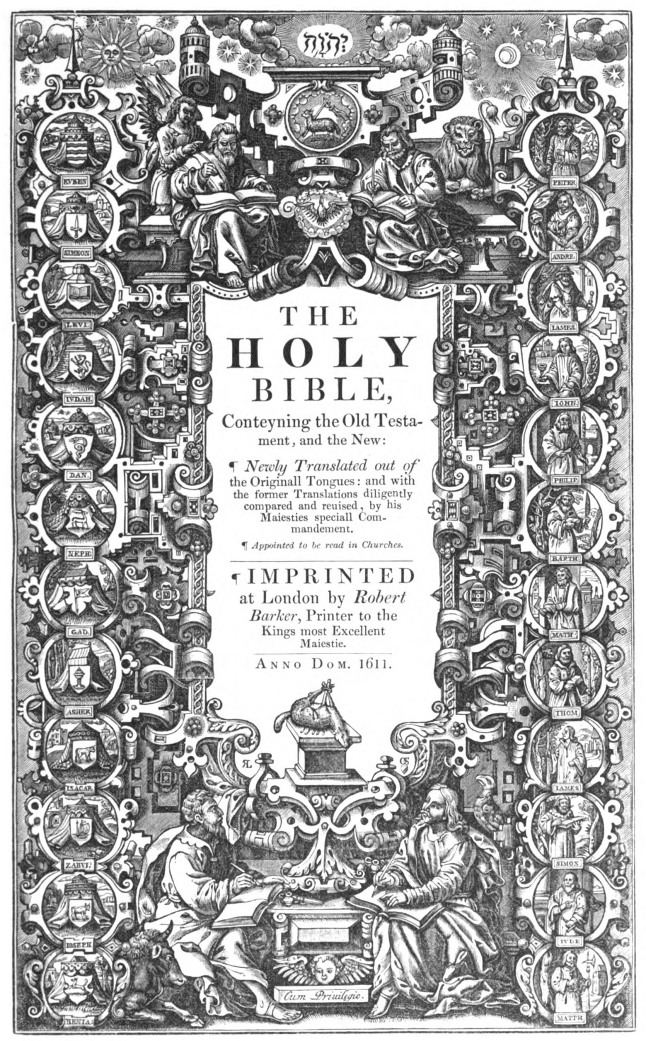

I really enjoy how busy this title plate is. Also how it’s like those old infomercials about various compilation CD’s for old people. “Remember the good old days when you’d spend the day cruising the beach and listening to golden oldies by Job and Ezekiel, but also the newer hits by Matthew and Luke!”

It should be pretty clear that these are deep waters and I am not really equipped to swim in them. That’s actually the conceit for The Waste Land Project in general, but it bears repeating. I am not particularly well-versed in Christianity, or religion in general. Yes, I read the entire Bible, but it was hard going and I will readily admit that not much of it stuck. That said, the purpose of this article isn’t to elucidate all 1800 pages of Biblical text. It’s to uncover the reason T.S. Eliot made certain references and hopefully bring about a slightly better understanding of his poem. I probably could have just read the particular books of the Bible that he references, but dammit, I’m not here to do things half-assed! Well, I am actually, but in a way that can point an interested reader in a deeper direction.

The strange thing is, at least early in the poem, the Biblical references don’t seem to be all that deep. There’s more going on with Tristan und Isolde. And that’s absolutely cool with me, because if I’m uncomfortable discussing medieval lit, I’m even more uncomfortable with this whole Bible thing. Of course my unfamiliarity didn’t stop me then and it’s not going to stop me now. I’m going to try and discuss the relevance of two Old Testament books that Eliot references, and we’ll see how it goes. The first is Ezekiel, the other is Ecclesiastes, and as I mentioned, the connections are slight. Unlike some of the other references in the poem, Eliot calls these out in his own notes, but really they’re just nods to the Scripture that Eliot goes on to mine for imagery. A heap of broken images, actually.

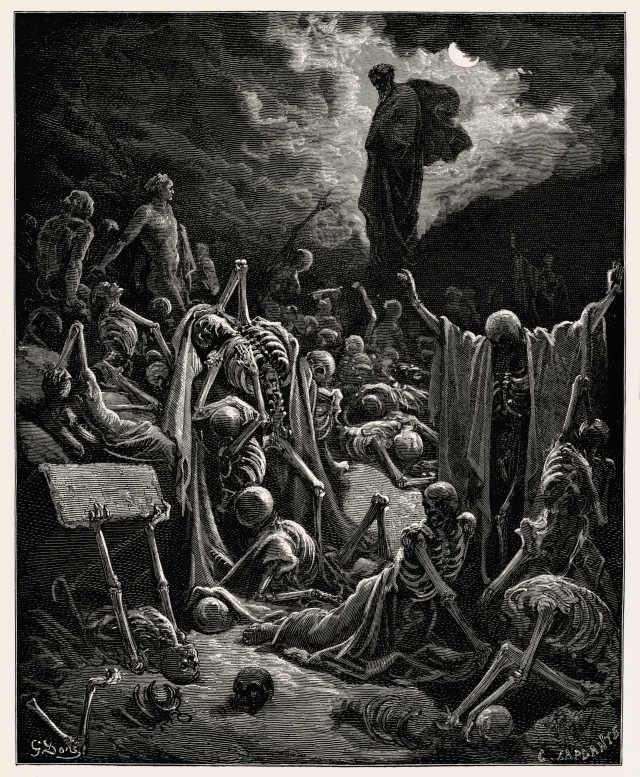

That’s more like it. “The Vision of Ezekiel,” a 16th century engraving by Giorgio Ghisi, which pretty much sums up the mood.

Discussion

Okay, let’s not dick around here. The following passage is, line-for-line, some of the strongest poetry in English. It’s ridiculous. Furthermore, all three of our Biblical references are hidden in the first stanza of this passage, so that makes our lives a little easier. I’m going to quote the whole thing though, just because it’s great and I feel like it.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no

relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

That last line, holy shit. Still gets me. Also, I would like to see an action movie where our hero is like an erudite John Wick and that’s his big kill line when he finally murks the villain. After killing all the henchmen and blowing up half the bad guy’s lair, he just gestures to the smoldering ruins and tells the bleeding, defeated baddie that he knows only a handful of broken images, and then points his gun at him, and says “now I’ll show you fear in a handful of dust, motherfucker.” Nobody write that movie, it’s mine.

Okay, so Bible stuff. The first reference, credited to Ezekiel 2:1, is the phrase “son of man.” Honestly, I’m not entirely sure why Eliot specified that instance, because it’s a phrase that comes up all the time. The actual passage is short and fairly common in the old prophet books:

“And he said unto me, Son of man, stand upon thy feet, and I will speak unto thee.”

And then the Holy Spirt bops into the unsuspecting goat herder or whatever and starts giving the poor bastard all kinds of terrifying visions of the apocalypse. In fact, that’s kind of the point of the next reference, which is given as Ezekiel 6:4. At this point, god has been going on about the faithlessness of Jerusalem, another extremely common thing, before saying:

“And your alters shall be desolate, and your images shall be broken: and I will cast down your slain men before your idols.”

And that’s it. Well, the next passage is pretty fucked. Let’s read it!

“And I will lay the dead carcases of the children of Israel before their idols; and I will scatter your bones round about your altars.”

Let’s just say that YHWH has a lot of anger issues. Now, according to my critical edition of the King James, Ezekiel is one of the more difficult to parse and understand of the books of the Old Testament, so that’s great. Suffice to say, it’s pretty clear that Eliot is doing a drive-by reference here in order to ground his own (broken) imagery. Most of Ezekiel is concerned with foretelling the total destruction and desecration of Jerusalem because of the usual idolatry-related grievances. The thing about Ezekiel is just how graphic these visions are. The two passages above are pretty standard for the entire book. It’s just the kind of desolate wasteland that Eliot is evoking with his own verse.

More Ezekiel, because the only imagery from Ecclesiastes I could find are comic sans inspirational quotes on rainbows and shit. This is “The Vision of the Valley of the Dry Bones” by Gustave Doré, and there’s your mood.

Okay, last reference, which is given as Ecclesiastes 13:5, but is 12:5 in my version:

“Also when they shall be afraid of that which is high, and fears shall be in the way, and the almond tree shall flourish, and the grasshopper shall be a burden, and desire shall fail: because man goeth to his long home, and the mourners go about the streets.”

Everyone dies, maaaan. Now clearly, there is a bit of mood-setting going on with these references. This passage is early in poem, in a section entitled “The Burial of the Dead.” The imagery here is dry and purgatorial, meant to evoke a landscape devoid of life save for the son of man and the unnamed, mysterious and spooky narrator. Eliot references a scene in Ezekiel which is a scene of total desolation, the images of idolatry broken to pieces alongside the broken pieces of Jerusalem. Not only is the city dead and dusted, but it deserved its fate. Meanwhile, the sun is beating and there is no water and there is no life, not even the minor life of crickets. The nod to Ecclesiastes is a nod to death and the failure of desire. Out of these ancient references, Eliot creates his red rock wasteland, a place beyond life but totally of the world.

This passage is an anchor of sorts for the rest of the poem. While The Waste Land is in many ways a poem about the wasteland of the modern soul and the emptiness of modern civilization, it’s also a poem about cultural tradition. Eliot was all about the canon and preserving civilization through culture. By leveraging the Old Testament in a deeply evocative and image-heavy section right up front, Eliot is able to ground his poem in the past. After all, humanity has been grappling with death and meaninglessness for thousands of years. Later on in the poem, Eliot explores these death instincts in the context of contemporary London and finds parallels all throughout history. This passage, with its Biblical roots, is the foundation of the entire rest of the poem, and ensures that for the myriad of other references and images throughout, The Waste Land is rooted in the historical, universal fears of death and desolation.